Writing is torture and it’s all I want to do

Thoughts on finishing the first draft of a book.

Yesterday I finished the complete first draft of my next book, tentatively titled Make Your Home in This Luminous Dark: Mysticism and the Art of Unknowing. (It will be published by Yale University Press; stay tuned for when.)

Whew. I scraped and clawed my way to get here. Some days I had to chain myself to the desk and just keep banging at the keyboard. Some days the words arrived like a song I’ve known forever. Some days I had to be gentle with myself. I tried to genuinely give myself permission to write a shitty first draft. I basically haven’t re-read anything I’ve written. There are some real rough patches in here. There are some placeholders where I just had to move on and not get bogged down.

I’ll now put the manuscript in a desk and not look at it for a month. I’ll probably try to rope a couple of friends into being “test readers” for me in the meantime, so that when I come back to it—hopefully with fresh eyes and ears—I’ll also have some feedback from others. For now, I’m grateful to have gotten to this point.

Having reached this stage, I’m reflecting a bit on the process. That has turned into some mid-life reflections on a career of writing. I share a few of these thoughts just in case it might be an encouragement or help to others.

There is no formula; there is no method. I used to feel guilty when I’d hear writers talk about their discipline of waking every day at 4:30am to write for two hours, or how they write 500 words a day, or whatever. I’ve published quite a few books and I have never had a daily practice like this.

I am what I’d describe as a “binge” writer. I research a book for 2, 3, 5 years sometimes—which means reading, scribbling notes & ideas, starting to conceive structure, etc. Then I write a proposal, sign a contract, and get a deadline. The deadline is king and tyrant (my wife hates this last stage). I am fortunate to have a profession that enables me to both buy and schedule huge blocks of time to devote just to writing. So I “write” a book in the six months or so before the deadline. Often that means, during a summer (aforementioned wife really hates that) or a semester when I’m not teaching, I show up to my desk every day by about 9am and write til 5pm (usually with a break for exercise). Some people will think this sounds absolutely horrible, and they’re not wrong, but this is my point: Do what works for you. You might be an “every day at 5am” person, or “200 words every damn day” person. Great. Godspeed. Let many flowers bloom. Find what works. For me, it’s this binge process.

This time around, though, I’d say I tried to hold even this schedule a little more lightly (I see that skeptical look on your face, Deanna). I could step away from the writing for a few days at a time without getting too anxious. I can see this now because, like a dork, I keep a record of my writing progress by day, word count total, and then daily word count. Here’s a peek at my tracking for this project:

If you care to look closely, you’ll see chunks away from my desk. It leaps from 8/16 to 8/23, for example, or 9/11 to 9/20. For me, this reflects a certain maturity—to not let a book rule my life. I hope it also reflects something I talk about in the book itself, which is cultivating a non-anxious posture to the world.

Every book is different. Your “process” might change from book to book, project to project. I’d say that for this book, I was surprised to find how much I kept reading and discovering during writing. I would show up with my notes for a particular section, find a little “note to self” about a possible link or trajectory, pick up a relevant source, and then get pulled in. I had to do a little self-talk to assure myself that I could spend “writing” days without my fingers constantly banging the keyboard. I think the book will be better for it. Relatedly:

Thinking is writing; reading is writing; diagramming is writing; writing is writing. In one sense, I “write” a book in about six months. In another sense, I’ve been “writing” this book for 5 or 6 years. These are related: I can only binge-write and hammer out a manuscript in 6 months because I’ve been writing in my head for 6 years. The Jamie banging at his keyboard is surfing on the Jamie who was reading, note-taking, sketching, and musing for years beforehand. If you take time with the research-writing, then you can trust yourself and find “flow” in the writing-writing.

Architecture is scaffolding, not destiny. I write with an outline. The book proposal has already crystallized something to that effect. In this case, I started working with the proposed Table of Contents as my structure. But as I was actually getting down to writing, my proposed architecture for the book was sort of puzzling me. It felt artificial and overly complex. I keep trying to work within it but was frustrated. Then I finally realized the proposed structure wasn’t going to work. I pulled back and re-imagined the outline—something cleaner, simpler. It clicked. I was off.

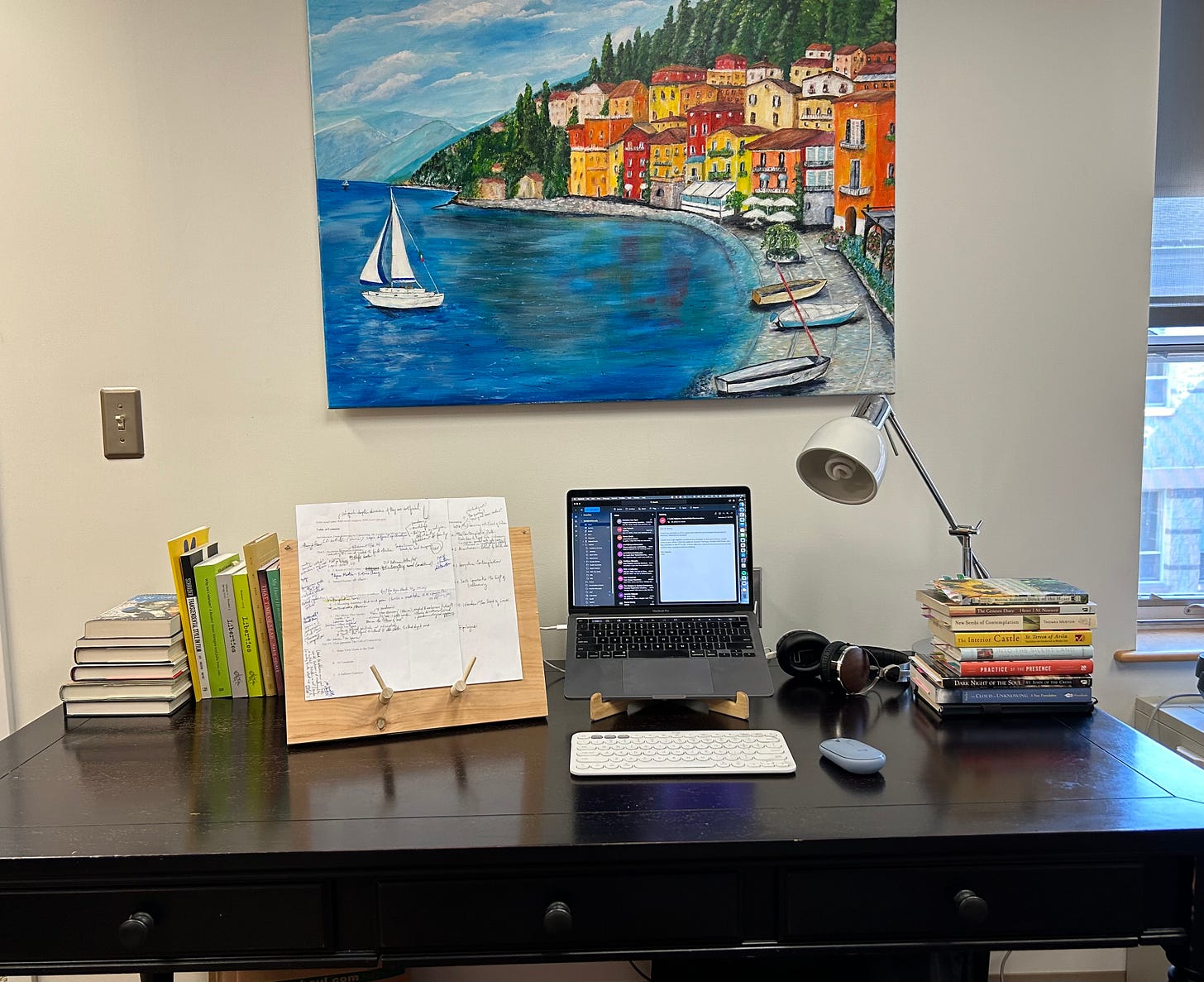

So the Table of Contents gives me a macro structure. Then, as I begin each chapter, I pull back and muse in order to come up with a working structure for each chapter. This time around, I’d say this took, on average, about a day. Again, I had to remind myself that this, too, is “writing.” I’d have three notepads and two screens and try to imagine a trajectory and draw lines of connection. I’d think out loud on these scratch pages until something began to congeal. For a project like this, sort of between scholarly and trade, I approached the chapter structure less as a syllogism and more like “beats” of an essay. Then I’d write down a structure in my Moleskin and prop it on my desk. This would be the scaffolding to guide me each day, section by section.

By the way, this is my working setup while I’m a visiting fellow at the Augustinian Institute at Villanova University. It’s worked great. (It’s a shared office, so the over-ear headphones have been a lifesaver.)

Tracking progress is both a carrot and a stick. As you saw above, I track daily progress. I’ve done this for years. I don’t know if it’s weird or not. I worry sometimes that it grew out of a sort of deep working class sense of guilt or shame that if I was just sitting at a desk all day I wasn’t really “working,” so I had to “show my work.” But in any case, I find it helpful. It externalizes a kind of self-accountability. It is a bit of a stick (how much did you advance the project today?) but also a carrot (on the days when you get to note big chunks of progress).

By the way, you’ll see some big leaps here if you look closely. Often those are days when I was able to cut and paste previous work into the manuscript. Another way of “writing” for 5 or 6 years is to turn other smaller writing assignments—e.g., magazine or journal articles, sometimes even lecture notes—into legwork and functional “first drafts” of material for your next book. I have done this from the very beginning of my writing practice.

Discovery is a delight. The absolutely best kind of day writing is the day that you manage to pen a sentence that you never imagined was in you, or end up chasing an idea you didn’t have before you sat down at the desk. All of the drudgery and teeth-pulling that characterizes writing is worth it for just these few moments of what almost feels like rapture. Yes, writing is torture, and it’s all I want to do.

Post Script

I’m en route to Whitworth University in Spokane, WA where my friend Davey Henreckson has organized a conference on the future of Christian higher education. I’ll be giving an opening keynote tonight. Davey’s wife, Elise, has just recently been diagnosed with an aggressive form of leukemia. Her care requires relocation to Seattle for 6 months. If you have the resources, would you consider joining me & Deanna in contributing to this fundraiser to help them in a terribly difficult time?

Anna Moreland, a friend who directs the Honors Program at Villanova, has just published a new book, with co-author Thomas Smith (Catholic U), called The Young Adult Playbook: Living Like it Matters. It’s a creative book that is the fruit of decades of thoughtful and care-full undergraduate teaching. I can imagine it being an excellent textbook at faith-based colleges & universities (though not only), especially in a wave of “vocation” courses at such schools.