James, the new novel from the ever-inventive Percival Everett, immediately deserves a place in that repository of the American canon we know as the high school English curriculum.1 And not only because of its masterful conceit: reimagining the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by giving a new voice to Jim, whom we meet here as the titular James.

It’s been a long time since I have gushed to friends about a novel, but I couldn’t stop enthusing about this book to anyone who would listen. Even while I was reading it, I felt a breathless wonder at what Everett was doing. The story retains all the swashbuckling pace of Twain’s adventures while, at the same time, operating on several meta levels–with respect to the racial (i.e., racist) history of the U.S. but also the mysterious alchemy of language, reading, and consciousness. To pull off such a plot-driven quest while also riffing on the death of the author is something the experimentalists of the 90s could never have dreamed.

And to top it all off: a plot twist (I won’t spoil it) that is, at the same time, an unveiling and an indictment of our collective history; but one that infuses a tenderness and affection that could almost make you imagine a different future.

James is, in a sense, built of books. His owners could never imagine the library could even be an object for him, but for James the library was the beginning of liberation. Armed with both double consciousness and an imagination fueled by reading, James is, in important ways, more human than his oppressors. Describing a library, James recalls:

I had wondered every time I sneaked in there what white people would do to a slave who had learned how to read. what would they do to a slave who had taught the other slaves to read? What would they do to a slave who knew what a hypotenuse was, what irony meant, how retribution was spelled?

Like a latter James (Baldwin), the narrator is an astute psychologist of his oppressors: survival means confirming their mistaken beliefs, abetting their convenient assumptions. And so James labors to hide his mastery of language and his capacity to read. This is easy enough to do, he realizes, precisely because reading is such a mysterious chemical reaction of the physical and the mental that can hide in plain sight.

I really wanted to read. Though Huck was asleep, I could not chance his waking and discovering me with my face in an open book. Then I thought: How could he know that I was actually reading? I could simply claim to be staring dumbly at the letters and words, wondering what in the world they meant. How could he know? At that moment the power of reading made itself clear and real to me. If I could see the words, then no one could control them or what I got from them. They couldn’t even know if I was merely seeing them or reading them, sounding them out or comprehending them. It was a completely private affair and completely free and, therefore, completely subversive.

This weekend we are remembering the centenary of James Baldwin’s birth, and I couldn’t help recalling this remarkable insight at the end of No Name in the Street while I was reading Percival Everett’s James:

Black is a tremendous spiritual condition, one of the greatest—this is what the blacks are saying [it was 1972]. Nothing is easier, nor, for the guilt-ridden American, more inevitable, than to dismiss this as chauvinism in reverse. But, in this, white Americans are being—it is part of their fate—inaccurate. To be liberated from the stigma of blackness by embracing it is to cease, forever, one’s interior agreement and collaboration with the authors of one’s degradation. […] When the black man’s mind is no longer controlled by white fantasies, a new balance or what may be described as an unprecedented inequality begins to make itself felt: for the white man no longer knows who he is, whereas the black man knows them both.

It is this knowledge that Everett performs in James.

With astute musings on language and literature threaded throughout the story, James is a kind of 4D chess. You can imagine a high school reader enthralled by the narrative while also experiencing inklings of the story’s political and historical subversiveness. But then you can also imagine the high school English teacher who unlocks this meta layer of the novel, thereby introducing young readers to the book all over again. This is the sort of critical thinking we need. The pedagogical possibilities are almost as thrilling as the novel.

I’m loathe to say much more than READ THIS BOOK because I want others to experience the joy and discomfort of being carried along by this story, like Huck and James on their fragile raft drifting down the Mississippi.

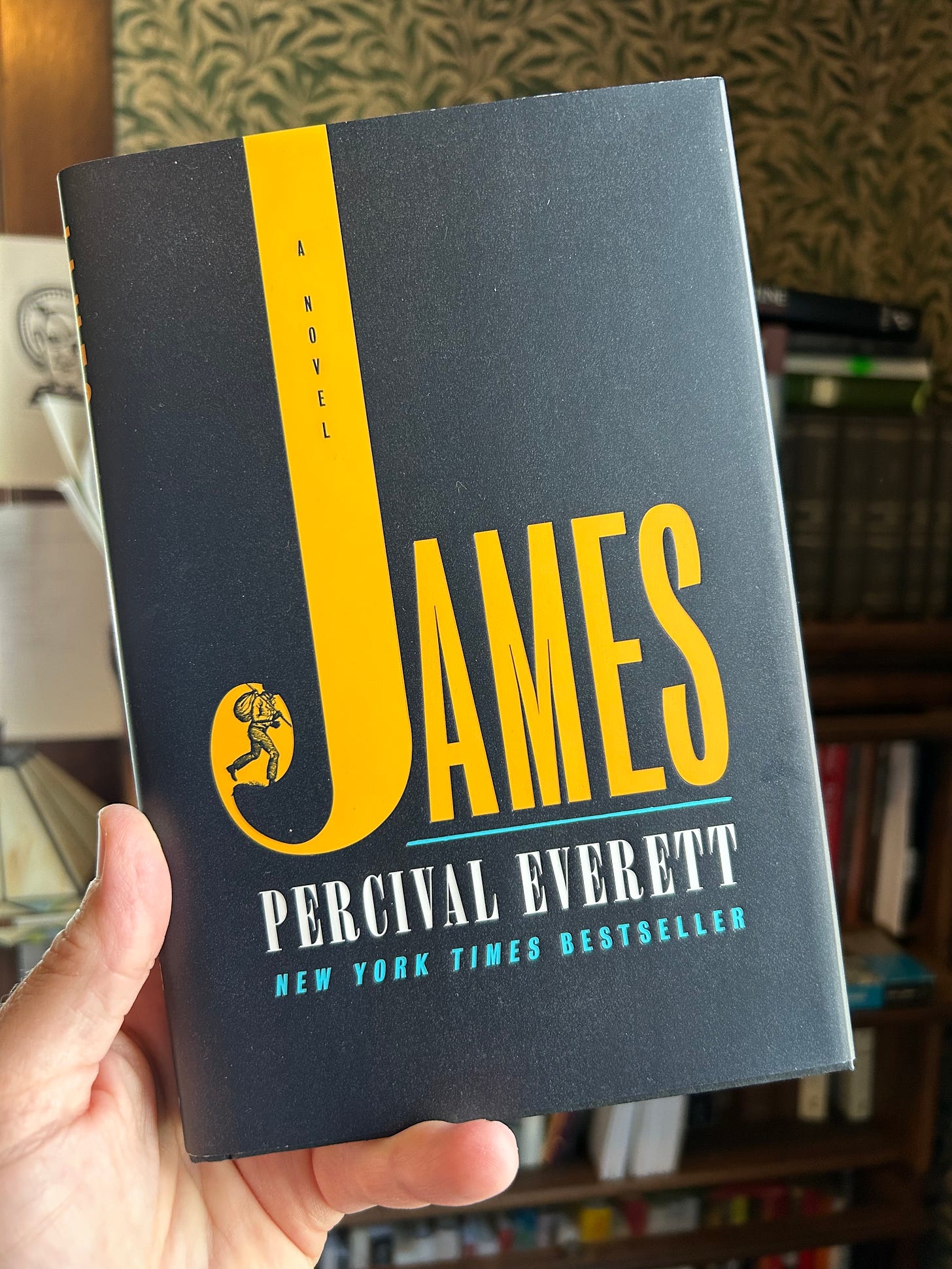

Doubleday also nails the materiality of the book in this regard: its trim size and typography hearkens back to old editions of Faulkner or Hemingway, so you feel like you’re already reading a “classic” somehow.