My youngest son, a film buff, is steadily building a familiarity with the canon of American classics. But I think he’d say that Paul Schrader is his favorite, which warms my heart since this is a love we share. (He & Schrader also share something in common: an alienating experience at John Calvin’s college). I’m jealous that he’s had the time and discipline to watch every bit of Schrader’s corpus. When we last saw each other, he couldn’t stop talking about Schrader’s 1978 film I’d never even heard of: Blue Collar.

Now I understand why. Set in Detroit in 1977, the movie centers on three characters who work at “Checkers,” a plant manufacturing taxis. (It took me a few beats to figure out why, in 1977, there were manufacturing cars that look like 1956 Chevys.) This creates a palette that is gritty and forlorn. In 1977, we are already past Detroit’s heyday. Smaller foreign vehicles have landed on our shores; we’ve been through one energy crisis and another is on the horizon; Ford Pintos are exploding. Schrader’s movie captures the malaise that Jimmy Carter will soon name in his infamous “crisis of confidence” speech.

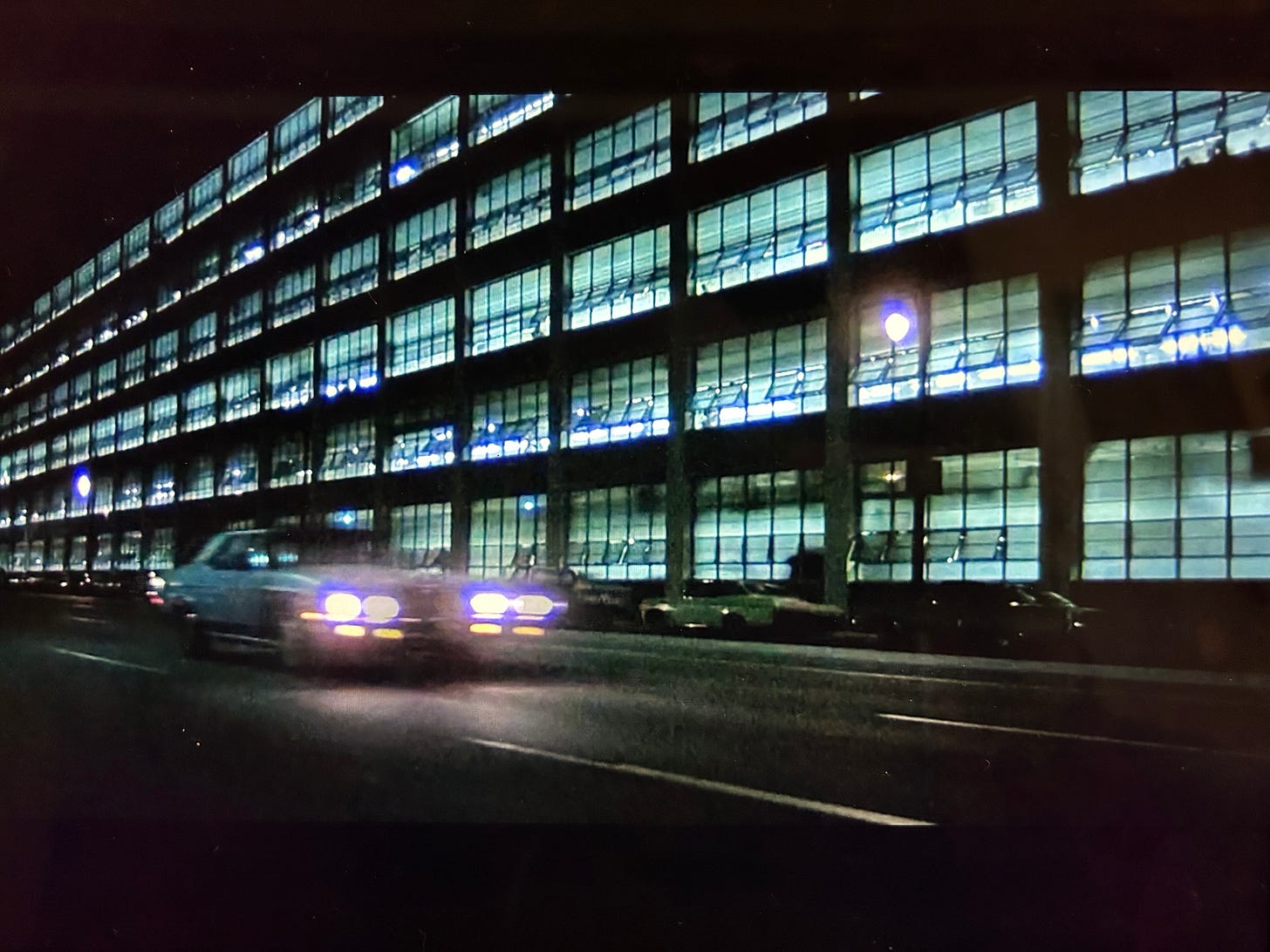

It was eerie watching Schrader’s Detroit, dominated by towering manufacturing structures that are now ruins or demolished (some of the structures I remember from my childhood when we drove through Detroit every winter to play hockey in Ohio). Near the end of the film, in an unnerving car chase where the score1 feels like nails on a chalkboard, we get a glimpse of one of these iconic factories alight. It’s hard to watch this and not see, at the same time, the scores of such buildings that now sit dark, all that glass shattered or gone.

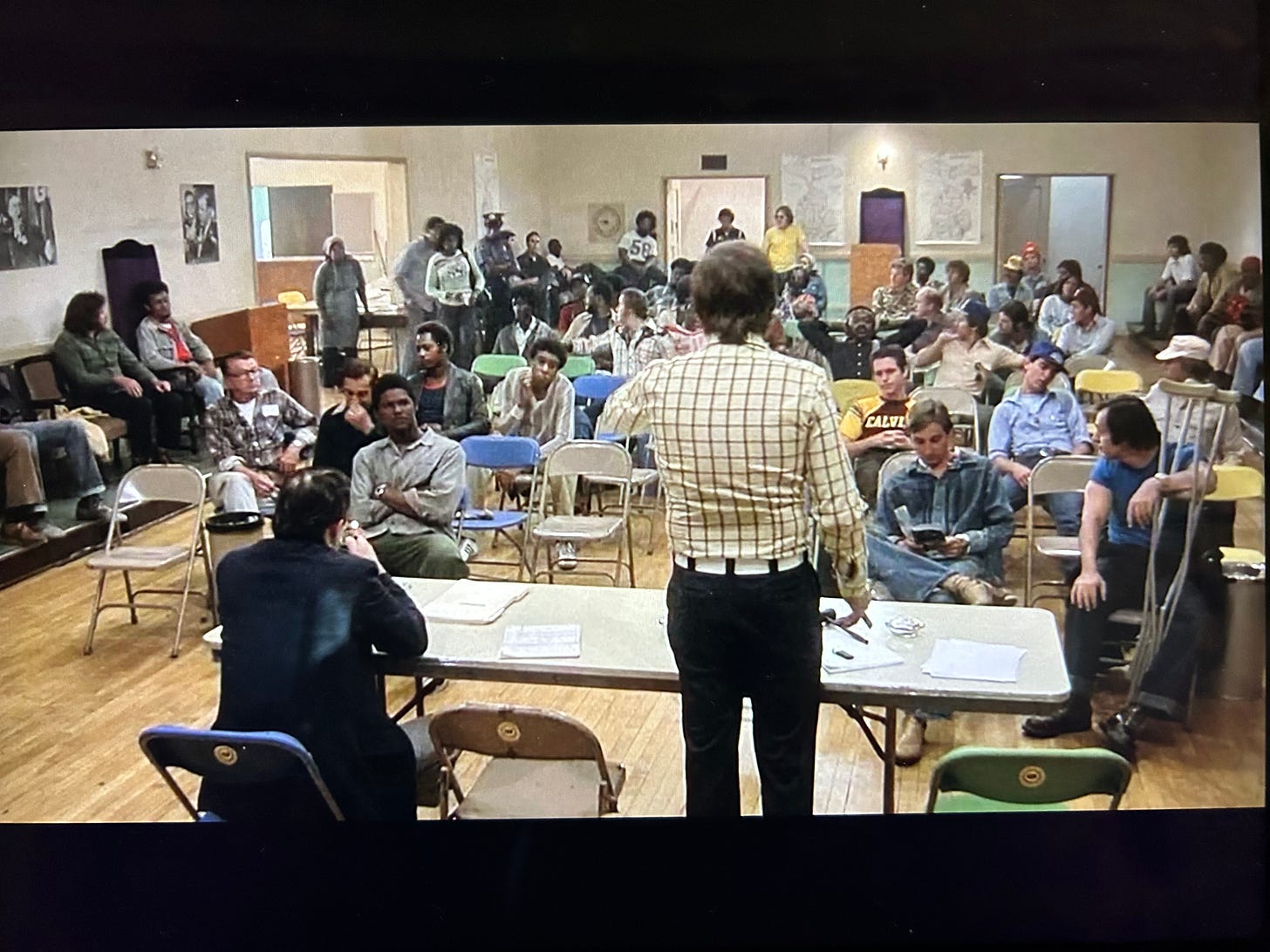

[Sorry, I couldn’t figure out how to screen-grab stills, so I’m reduced to taking pics of my screen.]

Richard Pryor, Harvey Keitel, and Yaphet Kotto give exceptional performances as three factory workers and union members who feel the pinch (or rather, stranglehold) of the economy in which they labor.2 Some of the best scenes—and shots—are languid moments where they share their most intimate fears and secrets. A confessional.

But this is no romantic portrayal of the beleaguered working class. As always, Schrader is an equal-opportunity offender. This is not a movie where organized labor gets to wear the white hat. That’s because Schrader’s critique of America is more radical: capitalism corrupts everyone. No one is pure. Where Mammon is lord, everyone becomes Its servant. The next time I teach Jonathan Tran’s incredibly important book, Asian Americans and the Spirit of Racial Capitalism, I want them to watch this movie.3

The racial element here is crucial. Schrader portrays an interracial friendship forged by class solidarity. If, in the end, the simmering, underlying racial differences explode in a way that is ugly and all-too-common, it is because Mammon wants a war of all with all. While some, watching today, will cringe at the N-word on the lips of a white character in a vitriolic confrontation, keep in mind that this movie also includes Richard Pryor’s passionate monologue about the realities of white privilege long before that’s what we called it. The movie demonstrates what Tran’s book is about: capitalism wants—needs—racism.

P.S. Schrader, playful and mischievous, plants a little Easter egg in an early scene where the Union members are meeting: a character wearing a Calvin College t-shirt. One might hope this gentleman had Nick Wolterstorff for a teacher and learned that Abraham Kuyper was a socialist.

Anticipating the sound & feel of the Card Counter soundtrack, decades later.

Unsurprisingly, especially at this stage of Schrader’s career, there are no compelling female characters.

There are a few scenes that will make this a little awkward. 😬 I’ll tell them to watch it at home on their own. I expect a few phone calls from parents. C’est la vie.