The noise of time & the "music of our being"

Complicity, compliance, corruption; comfort, conscience, cowardice

In Galileo’s day, a fellow scientist

Was no more stupid than Galileo.

He was well aware that the Earth revolved,

But he also had a large family to feed.

–Yevgeny Yevtushenko, “Career”

I have just re-read The Noise of Time by Julian Barnes.1 In free indirect style, we inhabit the mind and musings of the Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975). His career unfolds across the terror and heartbreak of the twentieth century. The young man lives through the Great War, the Revolution, and the Second World War. As we meet the middle-aged composer, he is smoking a cigarette in the hallway of his apartment building in the middle of the night, standing in front of the elevator with a case beside him. He has been doing this for weeks, hoping to spare his wife and children of the trauma of seeing him ripped from his bed by Stalin’s goons.2 So here he is again, in front of the elevator, waiting. And remembering.

Mostly what he remembers is the difficulty of negotiating his vocation as an artist under the capricious, philistine whims of what he simply calls “Power” (i.e., Stalin and, later, the “vegetarian” form of Power that is Krushchev). How to be creative when the price of admission is deference to a tyrant or a tyrannical ideology? (Manuscript paper, for example, is controlled by the Union of Composers.) How much does it cost to be able to do what you want to do—what you feel called to do, made to do, even—when that means paying a piper who wants you to dance a jig for the Leader or the Party? What if the price of your international “success” is your shriveled soul? What if, Shostakovich wonders in the end—what if surviving under such conditions is its own sort of death?

You might have guessed why I felt compelled to re-read the novel again.

But it’s not just the whims of the petulant would-be tyrant in the White House, with boot-licking henchmen (and -women!) carrying out his agenda. And it’s not just the disheartening example of elite and powerful institutions already groveling compliantly in order to secure the Capital they ultimately serve.

It’s also the petty tyrannies of mediocrity. It’s the despotism of middle managers who lack either imagination or courage but love to lord the little scraps of provincial Power they hold in their hands. It’s all the ways that our addiction to comfort makes us stoop to doing whatever Capital requires.

“Party” Lines

It’s the little reactionary men (sic) who see in a moribund denominational bureaucracy a place to claim a fiefdom. They connive to turn it into a sorry, gutted domain that reflects their spectacularly average, clichéd existence. With the thrill of control and fervor to dominate, they relish “draining the swamp” and revel in demanding compliance.

It’s congregational leaders who imagine “leadership” is synonymous with cultivating communities of fawning admiration. It’s pastors who hide their incompetence behind preening, sycophantic displays of “authenticity,” all while surreptitiously guarding themselves from real accountability and critique. It’s ministers who claim the “prophetic” mantle for themselves while sculpting a congregational ethos that allows only adulation of the party line. All “prophecy” must be directed outwards.

It’s the way college presidents at floundering institutions accrue emergency Powers for themselves by lurching from crisis to crisis, demanding the university remake itself over and over and over again. To dismantle the liberal arts college and rebuild it as a revenue-generating credential-machine, only one thing is necessary and only one thing is offered: urgency.3 Pointing out the external threats arrayed against higher education, college administrations “lead” from victimhood: they are victims of demographic trends, victims of market forces, and victims of the decision-making power of 18-year-olds and their families. Such victimhood becomes the ethos of the entire university which is now urgently mobilized to do one thing: survive. This is another way of saying that the entire university is turned into one massive enrollment division and marketing department. Every student represents urgently needed revenue. This, too, requires strict management of a party line. Don’t ask questions (“trust us”). All communication will be PR. Repeat said PR. Mute critique. Your survival depends on it.

A Fate Worse Than Death?

In The Noise of Time, Shostakovich gradually realizes that there are worse things than dying. In the middle of the novel, and the middle of his life, he worries about death. Sitting by the elevator, waiting for the henchmen to arrive, he pictures his disappearance into the iron bowels of Stalin’s meat grinder, never to be seen again.

But when he survives, the elder Shostakovich begins to realize: “He had lived too long.” His survival, in a sense, was more a torture than being disappeared. He had lived long enough to be fêted by the Party, to see the works they had rightly rejected now absorbed by the ideological machine. They could own him by celebrating him.

And that, of course, was the point at which the grabbing hands reached out towards him. See how things have changed, Dmitri Dmitrievich, how you are garlanded with honours, an ornament of the nation, how we let you travel abroad to receive prizes and degrees as an ambassador of the Soviet Union—see how we value you! We trust the dacha and the chauffeur are to your satisfaction, is there anything else you require, Dmitri Dmitrievich, have another glass of vodka, your car will be waiting however many times we clink glasses. Life under the First Secretary is so much better, would you not agree?

Later in his life, in a final act of humiliation, the composer is maneuvered into finally joining The Party. Only in retrospect does he realize his own naïveté about their wiles. He has been trapped. But the pincers won’t crush his existence; they will embrace him and gut him at the same time.

How, why had he not seen this coming? All through the years of terror, he had been able to say that at least he had never tried to make things easier for himself by becoming a Party member. And now, finally, after the great fear was over, they had come for his soul.

Barnes’ Shostakovich is no hero. He is not a martyr, nor a celebrated exile. There is no purity here, only the chronicle of an artist who—wrongly—imagined that irony was his defense. He starts each day by reading the Yevtushenko poem, “Career” (cited above) “instead of a prayer.” But this is not an act of centering conviction; it is an act of confession and penance. “‘Career’ was essentially about conscience; and his own accused him.”

This is the heart of The Noise of Time: it is really a study in conscience and cowardice. The Party won’t settle for ironic obedience. “They wanted your complicity, your compliance, your corruption.”4 (“You will learn to love Big Brother,” as Orwell put it so chillingly.) Which is why the ultimate question is one of courage and cowardice. And Shostakovich has a clear-eyed assessment of himself on this score. No excuses; no absolution. Just the remnants of inner turmoil that are a sign he has not been completely absorbed by the Party Line.

“He could not live with himself.” It was just a phrase, but an exact one. Under the pressure of Power, the self cracks and splits. The public coward lives with the private hero. Or vice versa. Or, more usually, the public coward lives with the private coward. But that was too simple: the idea of a man split into two by a dividing axe. Better: a man crushed into a hundred pieces of rubble, vainly trying to remember how they—he—had once fitted together.

Not all resistance is bravery, of course. Foolhardiness is a real temptation in such worlds—to go out in a blaze of self-righteous glory. Not all maneuvering is cowardice. Shostakovich keeps trying to find the line demarcating these things, mostly unsuccessfully. Some latecomers, he muses, arriving under “vegetarian” Power, did not know what it had been like.

Or what it was like to have your spirit, your nerve, broken. Once that nerve was gone, you couldn’t replace it like a violin string. Something deep in your soul was missing, and all you had left was—what?—a certain tactical cunning, an ability to play the unworldly artist, and a determination to protect your music and your family at any price. Well, he finally thought—in a mood so drained of colour and resolution that it could scarcely be called a mood—perhaps this is today’s price.

Shostakovich has no illusions about himself. But he is not without meaning or significance. He is not a nihilist. His art remains a redoubt. The music will live on, even the canned garbage demanded by the Party [“how much bad music is a good composer allowed?”]. Barnes draws this out with a beautiful thread that opens in a curious prologue and is then drawn taut in an epilogue. I don’t want to spoil that in hopes that you might read The Noise of Time. But I will close with one of Shostakovich’s musings on the way the work might live on.

What could be put up against the noise of time? Only that music which is inside ourselves—the music of our being—which is transformed by some into real music. Which, over the decades, if it is strong and true and pure enough to drown out the noise of time, is transformed into the whisper of history.

This was what he held to.

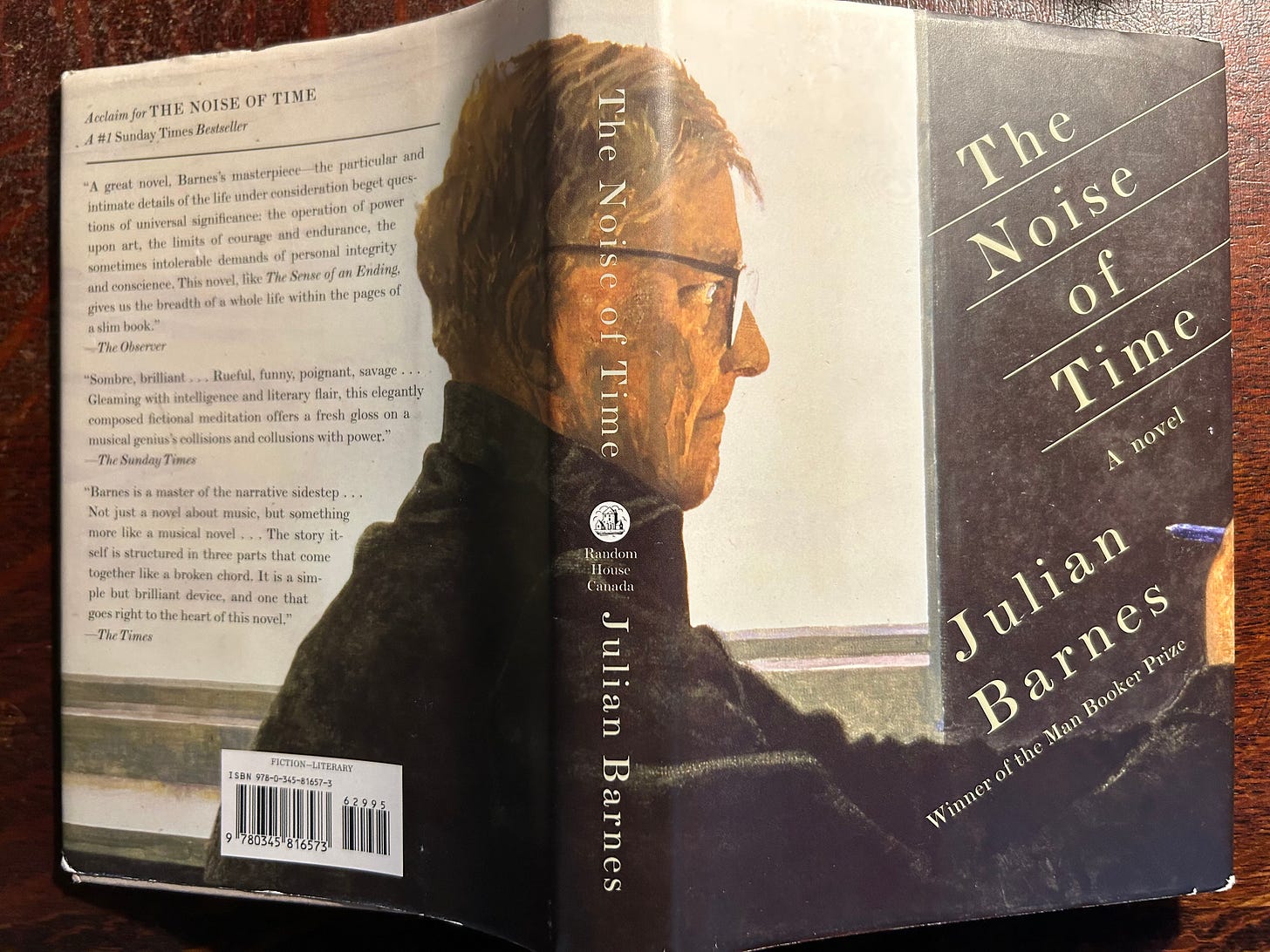

One of the losses of getting older is my inability to recall how books came into my hand. There was a day, when I was younger and my library smaller, when I could pick up virtually any book and remember where and when. Not so anymore. I’ve taken to scribbling places and dates in new acquisitions to try to stir my senior self. In this case, it seems I have a Canadian edition of Noise of Time, with this beautiful dust jacket, which means I probably acquired this in the summer of 2016 at Fanfare Books in Stratford, Ontario.

Trying to avoid, in other words, something like this.

The narrator, at one point, recalls a few lines of verse he came across in Turgenev’s letters:

Russia, my cherished mother,

She doesn’t take anything by force;

She only takes things willingly surrendered

While holding a knife to your throat.

One could say The Brutalist explores similar themes.