A couple of provisos out of the gate:

Andrew McCarthy’s documentary about the so-called “Brat Pack”—called, simply, “Brats”—would likely never have been made if we didn’t live in the era of streaming platforms scrambling for unending “content” to keep us tethered to our screens non-stop. There are all kinds of strange aesthetic choices in the film (camera angles, filters, etc) that are superfluous and distracting. My take here is not exactly art criticism. That would be a different essay.

I was born in 1970. When Brat Pack fame was at its height, I was fifteen years old, trying to figure out who I was and, like any fifteen-year-old, in the thrall of cool (and, let’s be honest, Molly Ringwald). The Brat Pack movies were both icons and mirrors for my generation.1 So when Hulu greenlighted this documentary, I was squarely in the bulls-eye of their demographic targets. And dammit, they were right.

Those qualifications made, I was surprised how much I kept thinking about this documentary.

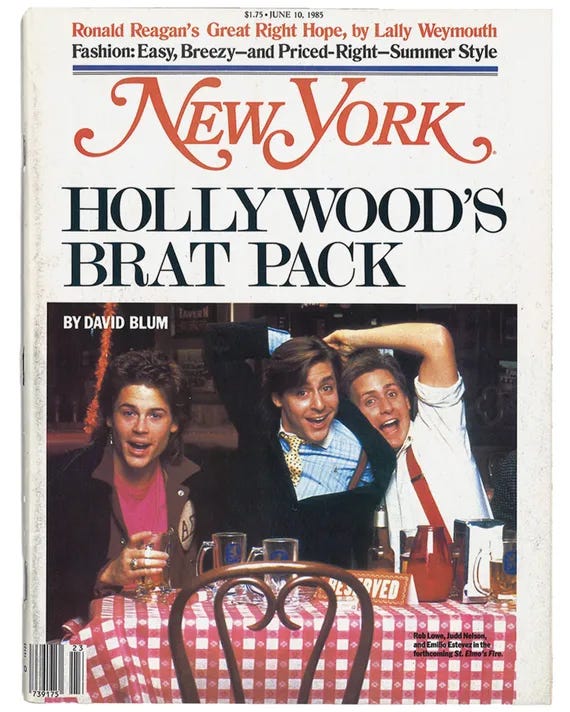

For those born in the 80s or later, let me set up the context. In June 1985, David Blum wrote a profile for New York magazine called “Hollywood’s Brat Pack.” It was a feature piece on a cadre of young actors who had taken Hollywood by storm, most recently in their hit movie, St. Elmo’s Fire. The cast constituted something like the inner circle of this collective of beautiful young things: Emilio Estevez, Rob Lowe, Molly Ringwald, Judd Nelson, Demi Moore, Ally Sheedy, Andrew McCarthy, and perhaps folks like Jon Cryer, Anthony Michael Hall, Timothy Hutton, and others.2 Blum gave them a name. Blum’s framing—cynically echoing the Rat Pack of Vegas fame, but dismissing these young actors as entitled posers and punks—was immediately appropriated by the wider zeitgeist. These actors would, henceforth, never not be members of this ignoble club.

McCarthy—a card-carrying member of the Pack—sets out to consider the fallout of this episode on the lives of young actors (most were in their very early 20s at the time). I realize that it might be hard to muster any sort of sympathy for people like Rob Lowe, Emilio Estevez, or Demi Moore, who went on to have successful careers. But those careers were different than they might have been, and I think this is what intrigues me about the documentary.

McCarthy, the director and “seeker” in the film, is, to my mind, the most sympathetic character. Even as a young actor, he was a little aloof. He was incredibly handsome, almost pretty, but would never be a Teen Vogue heartthrob like Lowe. He’s also one of the actors that, after this episode, kind of dropped off the map. Now 61, he is as handsome as ever, but you can tell he’s a little broken. The documentary is really just a matter of cameras accompanying him as he undertakes a therapeutic quest.

What you learn, very early on, was that the “Brat Pack” was a phantom. These young people, though often cast together, ran in different circles. There was no “pack.” And after the slam of the “Brat Pack” moniker, they avoided each other like the plague lest they fulfill Blum’s prophecy. When McCarthy begins calling them to talk to him about what happened, it is the first time he’s talked to some of them in over 30 years.

Granted, this sort of thing—the John Hughes movie clips, the soundtrack, the reverb of one’s teenage years—is pure nostalgic smack for Xers. So be it. But I think there’s more to it than that. I would almost describe McCarthy’s quest as spiritual. He’s trying to understand what happened, why Blum did it3, and most importantly: How did the others experience this? Most of them had never talked to one another about any of this. When the “Brat Pack” label stuck, these actors turned down opportunities to avoid being alongside one another in movies, as if they didn’t want to give Blum and the rest of the country the satisfaction. (He and Estevez discuss this in particular.)

If I describe McCarthy’s quest as “therapeutic,” that is not meant to be at all dismissive (sad that one has to make that explicit). McCarthy has clearly carried wounds since 1985. He was hurt, but also befuddled, confused. What I find beautiful in the film is the way that talking to one another about it is not just cathartic but generative. You can see McCarthy acquiring new frames, new angles, fresh insights that perform a kind of recollective restoration. I’ll confess my take on Demi Moore was transformed by this documentary; having spent a life in recovery, she is sage to McCarthy’s seeker.

My wife and I were both impressed at how articulate these young actors were at the time, in 1985. They were constantly asked about the “Brat Pack,” and you can see their exhaustion and disappointment. They want to talk about their art, their craft, and when they do, they are reflective and insightful. They were just so young, and seeing people now my age slagging on them and piling on these kids is both gross and angering. America eats its young.

There is one other thread of the film that I found poignant. I think this is what has kept me thinking about it. It’s something that non-artists might find hard to understand.

It’s clear that McCarthy, but not only McCarthy, had his career derailed by this episode. He is mostly hurt and sad, but there is a subtle rage restrained under the surface. And I think what he most resents is the way he was never able to overcome his early success.

At the heart of being a “creative,” I think—an artist, a writer, a filmmaker, etc—is a profound desire to do it again, but differently. To make something new. This is the difference between the artist and the hack. The hack is delighted to hit upon the “bestselling” formula and just keep doing the same thing over and over. You can make a lot of money by giving an audience what they already like. Lots of readers and viewers want the comfort of the same thing over and over again.4 The artist, however, would rather die or close up shop. For the artist, every new project needs to find its own audience—needs to make its own audience. This is why you will hear writers talk about “writing for themselves,” I think. They are not obeying some demand of the market but the compulsion of that inner daemon that has whispered a vision for something the world hasn’t seen yet.

Or, to put it negatively: the true artist works under the burden of not being defined by what they have done. As a writer, for example, I live in the constant hope that the next book is better. I try to remain grateful for the books I’ve written, and for the warm, meaningful responses they garner from readers. But I would share Andrew McCarthy’s sadness if I thought I’d already written my best book. Even if it might be true, I have to live as if it’s not. (I really, really hope it’s not true.)

I think this is the deep sympathetic resonance I felt with the “Brats” doc; it was really a sympathy with McCarthy and this burden of the artist enduring over time. I hope the exercise was healing for him. And I hope, with this film, he feels the joy of having made something new.

Oof, is anything more 80s than that John Parr music video? Cringe. But we were so earnest.

The overwhelming whiteness of this crew, and the movies they starred in, becomes a topic of conversation in the documentary.

Spoiler: he confronts Blum at the end; I won’t say more.

Hence the indomitable place of the “franchise” in the contemporary movie industry.